In one of Aesop’s fables, a mighty tree boasts to a little reed, “Who shall pluck me by the roots?” Straightaway a powerful wind blows and uproots the tree, and the little reed, able to sway in the wind, remains in place. The moral: there is an upside to not standing out. Glancing at the Beatitudes opening the Sermon on the Mount, we might evince a similar moral at play in Christ’s words “the meek shall inherit the earth”.

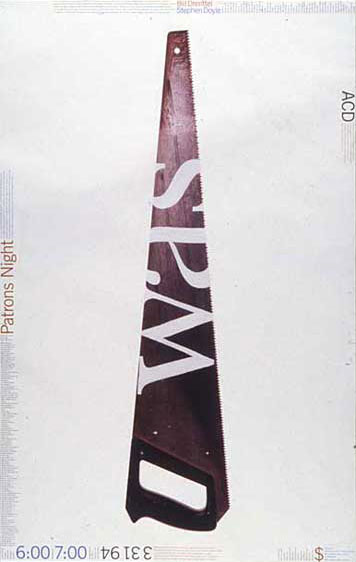

However, is this the same Jesus who once praised John the Baptist for his fatal criticism of Herod Antipas’s adulterous dealings? (For this stance, John’s head was cut off and brought to Herod’s court on a platter). Before the masses, Jesus ironically contrasted the teaching style of their conformist religious leaders with that of John the Baptist’s by asking, “Who did you seek out in the wilderness, a reed swayed by the wind?”[1]

Jesus owned an uneasy style for a moralist of his time (above is not his only stiff maneuver on Aesop). The Sermon on the Mount, both in our time and his audience’s, stands out among his unnerving strings of sayings. Still, a habit in our day is to regard Christ’s estimation of poverty and humility, and especially his saying to “offer the other cheek”, as prompts to passivity. (Is it an accident that the cantankerous philosopher Nietzsche regarded Christ’s call to love one’s neighbor as so much saccharine egalitarianism?) But to an audience under the thumb of Roman oppression, the tack of love carried a certain revolutionary zing. Jesus made that clear by giving ingenious expression to the Torah’s extreme valuation of human dignity.

From the starting blocks of the Law, Christ’s Sermon on the Mount elevates the worth of common-folk humanity to heretofore-unknown majestic heights. Every thinker who has ever read the Sermon has noted Jesus ratcheting up our responsibility to the precepts of the Law. Actually, he is pumping at the lever of human dignity. Using his poetic, Eastern homiletic style, he elbows out human presumptions about the awkward aloofness of God. God clothes the grass with the “lilies of the field” (a Hebraism), but He wraps the children of God in greater finery. Here, the sublimity of Solomon’s raiment is appraised as far inferior to the splendor of human flesh (I’m not kidding!). With Jesus, the wheeling swallows are evidence of God’s relentless decency. In this manner, Christ brings pungent questions to his audience’s trust in the guileless fatherhood of God. He draws attention to the bad habits of hypocrisy, self-advancement and gentile fatalism and worriment to undermine God’s life-giving overtures. Along the way, he drops some stunners – for example: “You must be perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect”.[2] In other words, “There must be no limit to your goodness, as your heavenly Father’s goodness knows no bounds”, as the New English Bible perfectly translates this.

Such moral insights remain unparalleled in the history of ethical discourse (we saunter along throughout our days in the West unaware how indebted we are to this sermon of firsts). Christ’s sayings once provoked an Israeli scholar of Early Rabbinics at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem to remark, “These are at once simple and profound, naïve and full of paradox, tempestuous and yet calm. Can anyone plumb their depths?”[3] Another scholar I met in Jerusalem, an expert in the 900 some parables that appear in ancient Jewish literature, remarked that the parables of Jesus easily rise to the foreground of her studies (and, implicitly, her Orthodox Jewish experience). According to her, Yeshua seems to have no peer in Rabbinic history in his homiletic effectiveness with the parable form, namely to draw out the ethical dimensions of the Torah and frame a multi-faceted response to it.

In fine Rabbinic fashion then, Jesus concludes his Sermon with a call to urgent authenticity by telling the parable of the two house builders (perhaps also a thump number on Aesop above). In the parable, “doing” (in addition to “hearing”) invokes the unshakable stance of the Kingdom of God against a violent world. Christ invites his hearers to dare the goodness of God by bringing their new outlook to bear on human activity (living life without setting limits to one’s goodness, apparently, opens up the opposing equivalent of Pandora’s box – the storehouses of God’s exuberant goodness). One can understand here the total punch of the Sermon: what follows the Beatitudes in the next three chapters is a well-built elaboration on the estimation of humility, God-trust and authenticity to aggravate “certainties” in the face of indifference, brutality and the mundane rewards of convention. This is no mere sentimental teaching. Jesus, after all, identifies the mourners, the broken-spirited and those who hunger and thirst for justice (Ts’dakah) not as victims. From God’s vantage, they are the overcomers. Understood this way, the Beatitudes suddenly become unnerving – you might even say that they are Christ’s clarion call to engage the fight. There is no succor here for “supporting the burden of existence” (as Nietzsche claimed) except to encounter it brazenly.

Like a mythic haze, or an arcane poem, the strong, overcoming aspect of Christ’s message seems to have remained only ephemerally present or obscured in the mounds and valleys of Christian history, except in the blaze of a saint’s life here and there (as with the life of St. Francis). A young Indian lawyer and civil-rights activist in South Africa finally rediscovered the strong aspect of Christ’s message only a little over a century ago. To change the course of human events through nonviolent resistance and appealing to the humanity and reason of one’s overlords (interestingly, with their own sacred text providing the ironic inspiration: “Do not resist an evil person”[4]) was an insight that had evaded Western intellectuals up to that time. Drawing inspiration from the Sermon on Mount, this non-Christian lawyer, Mahatma Gandhi, did not consider his political tactic of nonviolence as the weapon of the weak. In fact, he argued for its distinction from the misleading labels of “passive resistance” or (minority) “suffrage”. He called it instead “truth-force” (or “love-force”): the unblinking insistence on truth in patiently dispelling your opponents’ false constructs of life. Gandhi had understood that, with Jesus, love played on the offense. Only until the mid-twentieth century, and only in reflection of the life and thought of Gandhi after the emancipation of the Indian subcontinent, did the West recover an understanding of the strong aspect of Christ’s message. Through the leadership of Martin Luther King, Jr., who adopted Gandhi’s lessons in another civil rights movement, the love-force of Jesus was nudged back to the foreground of Christian history.

With easy conviction, I believe that Jesus was smiling at the Gandhis of history, both renown and unnamed, when he first uttered the Beatitudes. Nietzsche had assumed that only the pitiless Superman would transform history this devastatingly, and the last place Nietzsche would have looked for the kernel of that transformative power was in the words of the Sermon of the Mount. But today, our backs stiffen when we encounter pairs of drinking fountains labeled “white” and “colored” in museum displays. Our head shakes uncomprehendingly at that salt and pepper reality less than 50 years ago when this kind of daily degradation of human dignity was a certainty of human existence. So strong has been that overcoming, the mammoth in the natural history section seems as hoary as these relics.

[1] Matthew 11:7

[2] Matthew 5:48

[3] David Flusser, The Sage from Galilee: Rediscovering Jesus’ Genius, (Eerdmans: Grand Rapids, MI, 2007), p. 30.

[4] Mathew 5:39

No comments:

Post a Comment